Survivance Art - The " Indigenous Art Exhibition Area " at 2025 ART TAIPEI

Curator | Manray HSU

The " Indigenous Art Exhibition Area" at ART TAIPEI has entered its sixth edition this year (2025). This edition is themed "Survivance Art," responding to the cultural loss caused by long-term colonial rule and assimilation policies faced by contemporary Indigenous peoples, and to the cultural revitalization conducted under legitimate grounds since democratization. Contemporary artistic creation has thus blossomed and borne fruit in the 21st century.

The English term survivance is an archaic form of survival, but as a concept, it was proposed by the Anishinaabe Indigenous cultural theorist Gerald Vizenor. It refers to “an active sense of presence, the continuance of Indigenous historical narratives, rather than a mere reaction or the

simple fact of survival.” It emphasizes the proactive and vital attitude of contemporary Indigenous peoples, going beyond mere survival in the ruins of tribal cultures. Creativity in art is a crucial element here, as further elaborated by the Cherokee poet Diane Glancy: “sur-” means beyond survival, and “-vivance” means vitality. Therefore, survivance is not only surviving or living but also signifies resilience, perseverance, and ongoing vitality.

Vizenor extensively employs poetry, stories, myths, and historical texts to demonstrate how Indigenous peoples in the Americas intervene in mainstream discourse through narrative practices, resisting the fixed stereotypes imposed by settler colonizers. His notion of the “postindian” denotes a cultural condition that transcends colonial constructions—it deconstructs and negates colonial labels and foregrounds the Indigenous-led cultural identity regeneration and transformation based on their own history and cultural background. From the perspectives of Taiwan and global indigenism, the turbulent Indigenous movements since the latter half of the twentieth century have not only reversed the decline of Indigenous multicultural traditions in dominant narratives but also sparked a new wave of cultural revitalization. This has culminated in the unprecedented flourishing of contemporary Indigenous art seen today.

Over the past decade, the number of Taiwanese Indigenous artists has steadily increased, with works becoming richer and more diverse, gaining international attention and invitations to major global biennials and triennials such as the Asia Pacific Triennial, Sydney Biennale, Yokohama

Triennale, Gwangju Biennale, Sharjah Biennial, as well as the Venice Biennale and Documenta in Germany. Domestically, events like the Taipei Biennial and the Taiwan Biennial have also become key platforms for Indigenous contemporary artists to showcase their talents.

This year's " Indigenous Art Exhibition Area " features five artists: Siki Sufi (Amis), Laluyu Pavelav (Paiwan), Eleng Luluan (Rukai), Milay Mavaliw (Puyuma), and Idas Losin (Atayal and Truku).

As the first quarter of the twenty-first century draws to a close, this group of artists largely grew up experiencing the Indigenous name recognition and land return movements of the 1980s and 1990s. Throughout the process of cultural revitalization in their communities, they frequently

traveled between their ancestral villages and urban centers. They have inherited the traditional cultural foundation as creative nourishment, while simultaneously embodying urban modern experiences and possessing an international perspective. Their artistic formation has largely depended on everyday cultural activities in their communities—immersed in traditional rituals,mythological motifs, clothing, and architectural crafts—without the typical imprint of contemporary art academy pedagogy. Even for those who have undergone formal academic training, personal creativity and the influence of tribal culture have enabled them to break free from institutional constraints and develop distinctive styles. These representative creators have reached maturity in media, techniques, and personal styles, serving as a cross-section of this era. They bear witness to the arrival of a new, mature creative period following the tentative emergence of Indigenous contemporary art in the 1990s. The concept of “Survivance Art” signifies that these artists not only embody the resurgence of new life after enduring a painful history but that their works themselves possess the power to narrate these complex and subtle stories.

Siki Sufin (Chinese name Liao Yi-sheng) (Amis) grew up during the era of Indigenous movements in the 1980s and 1990s, and like most of his peers, began frequently moving between tribal villages and cities. Working on construction sites, he faced language barriers between different Indigenous languages, but speaking Mandarin was the safest and most reliable means of communication. After the "awakening" of that era, he decided in the late 1990s to return to Dulan. This homecoming sparked his creative impulse. He was successively enlightened and influenced by mature East Coast artists at the time, such as Rahic Talif, A Shui (Chen Zheng-rui), Lin Yiqian, and Hagu. He entered the world of woodcarving, integrating Amis culture,

mythology, and legends into his work. Around 2003–2004, he became moved by the elders in his community who had served in the Takasago Volunteers under Japanese colonial rule and as Taiwanese veterans conscripted by the Nationalist government to fight in the Chinese Civil War

after World War II. Their stories had gradually become forgotten as a "dark history." Many had gone to battle at a very young age and died far from home. The woodcarvings exhibited in this show mainly derive from this series. The work "Mother Earth" depicts a mother raising a feathered crown to crown the young warriors who never reached adulthood. Other works such as "Wings to Take Me Home" draw on an Amis song: "Friend, please bring me a pair of wings to take me home, my friend," expressing the soul’s plea for wings to fly back home from wandering in foreign lands.

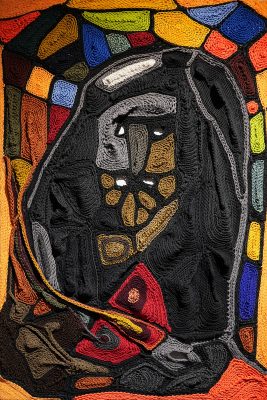

Eleng Luluan (Chinese name An Sheng-hui) (Rukai) was originally from Kucapungane Village. After 2002, she relocated to Dulan, Taitung, and currently resides in Taimali. As a member of the Rukai aristocracy, she was immersed from a young age in weaving and other deep cultural heritage practices. Active in Taiwan’s contemporary art scene since the late 1990s, her work focuses on cultural loss, colonial trauma, contemporary ecological imbalance, and the rumination of personal experience, especially from the perspective of an Indigenous woman navigating life beyond her ancestral community. Whether through large-scale installations or small-scale works, her art evokes introspection, condensation, and a sense of unspoken restraint. The works exhibited this time center on wooden-frame weaving. Through intricately layered crochet techniques, she constructs complex imagery and metaphor. The series “The Place Where Water Dwells: A Vanished Site” comprises five small pieces that depict what appear as contour lines connecting mountains, water, flowers, and plants, yet these ancestral water

sources can no longer be seen following environmental changes and destructive debris flows. In “Who Am I” a massive figure with its back to the viewer dominates the composition like an invisible force of life or destiny, representing the artist’s existential self-exploration as she merges long-accumulated anguish and radiance into a structurally dynamic picture. The “Somnambulist Trilogy” is a deeply personal work presenting several persistent sleepwalking states she has experienced over the years: “The Bridal Chamber Night in Kucapungane (Childhood Sleepwalking),” “The Water Tap in Wutai (Migration and Family Memory),” and “The Enchanted Forest Following the Hunter at Night (Awake Sleepwalking Sensation).”

Milay Mavaliw (Chinese name Zhou Meiling) (Puyuma) spent her childhood in the Katratripulr (Zhiben) Village. After becoming a professional athlete, she went to Japan to study interior design. Working in the design industry for a long period, she found her creative desires unmet and turned to art in the past decade to sincerely confront her own existence. While studying in

Japan, she realized her limited knowledge of her Indigenous cultural roots. Therefore, her artistic practice emphasizes the expression of original patterns. Through her acute sensitivity to color and form and delicate textures, she has developed a distinctive painting style. Raised in the community, she is also skilled in woven installations and integrates the tactile experience of weaving into her painting. Hence, her painting often appears as woven, which she calls “weaving painting.” This exhibition features her “Totem Ballad” series, including the “Weaving Painting Series” and the “Gathering Series.” Totems generally refer to ancestral spirit images of various Indigenous groups, which incorporate the connections between humans, nature, and the cosmos found in founding myths. The Totem Ballad represents these patterns woven into songs, symbolizing “memory, unity, inheritance, and hope” expressed in tribal daily rites such as the Harvest Festival and Ancestor Worship. The trembling brush strokes portray the life courses of individual tribe members. From the personal to the collective, and from the tribe to urban, national, and cross-species societies, Indigenous survivance continues to be inherited through these patterns.

Laluyu Pavelav (Paiwan) was a migrant construction worker in his youth. After returning to his community, he became a self-taught woodcarver within the strong and rich woodcarving culture of central Paiwan. He founded the “Woodpecker Art Workshop” and likens himself to a woodpecker that breathes new life into traditional cultural deadwood, symbolizing the artist’s transformation of decay into marvels. Currently, he is a cultural preserver appointed by the Ministry of Culture, responsible for the transmission of tribal crafts. He exhibits a series of Paiwan ceremonial knives and ritual drinking vessels, which demonstrate his most remarkable

craftsmanship. Among Taiwanese Indigenous peoples, several groups have a “ceremonial knife” cultural tradition. These knives are not only practical tools but also carry important symbolic meanings related to coming-of-age ceremonies, social status, and cultural significance. Paiwan ceremonial knives embody ritual and talismanic concepts; their sheaths are often inlaid with exquisite carvings and symbolic motifs such as the sacred hundred-pace viper totem. The ceremonial knife functions as a symbol of male adulthood and social rank, as well as having protective and blessing connotations. Paiwan society has a strict hierarchical system, and the

ceremonial knife represents status, holding an irreplaceable core meaning within ethnic identity.Laluyu Pavelav’s knife carvings are finely detailed, adept at three-dimensional sculptural work featuring traditional Paiwan totems—such as the hundred-pace viper, human figures, and flora and fauna patterns—manifesting the sacredness and aesthetic of traditional culture. He also uses skillful visual tension to project contemporary spirit. His works commonly employ hard yet carvable woods like jackfruit wood, combined with traditional colors such as vermilion, black, and white, emphasizing multi-layered visual effects on handles and sheaths.

Idas Losin, of Truku and Atayal descent, grew up immersed in her community’s cultural milieu.She graduated from the Department of Fine Arts at Taipei National University of the Arts, beginning her art career in 2001. Proficient primarily in oil painting, her works combine strong autobiographical elements with concern for land and environment, successfully integrating Indigenous symbols with contemporary artistic language to create images representing contemporary Indigenous presence. She transforms elders’ life experiences, ethnic histories, and cultural norms into painting themes that express ethnic identity and life philosophy. She especially focuses on cultural elements such as Ptasan (facial tattooing), Tminun (weaving), and Gaga/Gaya (tribal laws), using the “text” conveyed by weaving patterns as a creative inspiration. She reinterprets these traditional motifs through painting as an artistic language for exploring self and cultural connection. Her distinctive style features bold, pure, and vivid colors—such as the reds of the Atayal, the whites of the Truku, and the dark tones evoking nature’s night and ocean—drawing viewers into the spiritual cycle and contemporary vitality of Austronesian cultures. In 2012, her work The Symmetry of Body and Soul juxtaposed figurative modern objects with abstract weaving patterns, expressing the interplay between tradition and modernity, as well as between reality and illusion. Since 2013, Idas has continuously advanced her “Island-Hopping” project, traveling to multiple Austronesian island communities throughout

the Pacific—including New Zealand, Tahiti, Hawaii, and Guam—broadening her understanding of Austronesian cultures and colonial histories from an international perspective, further highlighting the cross-cultural dialogue and global themes in her work. She won the Pulima Art Award Grand Prize and has exhibited at the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Kaohsiung

Museum of Fine Arts, the Museum of Contemporary Art, as well as internationally in Australia,France, the United States, and participated in significant events such as the Asia Pacific Triennial in Brisbane and the Sydney Biennale, demonstrating her influence on the global art stage.